EXHIBITION DETAILS

Portfolio Showcase Volume 9

Artists:

Bob Avakian, Robert Crifasi, Leah Edelman-Brier, Jessica Harvey, Clay Jordan, Michael Joseph, Elise Kirk, Suzanne Revy, Camilo Ramirez, Jessica Eve Rattner, Susan Rosenberg Jones, Joseph Stanek, Kathleen Taylor, JP Terlizzi, Leah Zawadzki

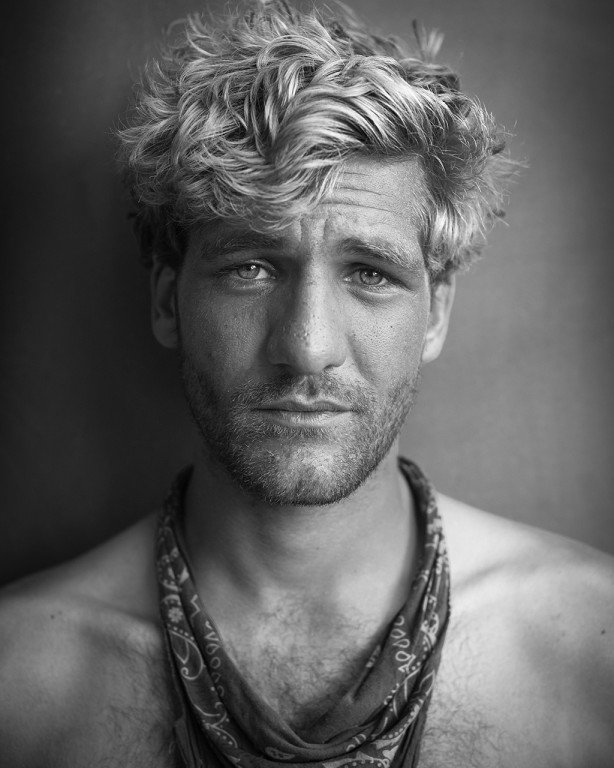

Bob Avakian

Lost and Found is a portrait series that examines the individual souls of lost youth who abandon home to travel around the country by hitchhiking and freight train hopping. Within their personal journey driven by wanderlust, escapism or a search for transient jobs, they find a new family in their traveling friends. They are photographed on public streets using natural light, in the space in which they are found.

Like graffiti on the walls of the city streets they inhabit and the trains they ride, their bodies and faces become the visual storybook of their lives. Their clothing is often a mismatch of found items. Jackets, pants and vests are self-made like a patchwork quilt, using fabric pieces of a fellow traveler’s clothing embellished by metal bottle caps, buttons, safety pins, lighter parts, syringe caps, and patches. The high of freedom however, does not come without consequence. Their lifestyle is physically risky and rampant with substance abuse.

Each traveler’s story is different, but they are bound by a sense of community. Often unseen and mistaken by their appearances, they are some of the kindest people one might meet. Their souls are open and their gift is time. As one states, “They will give you their time because time is all they have.” And in some cases, in the family they have lost, they have found each other.

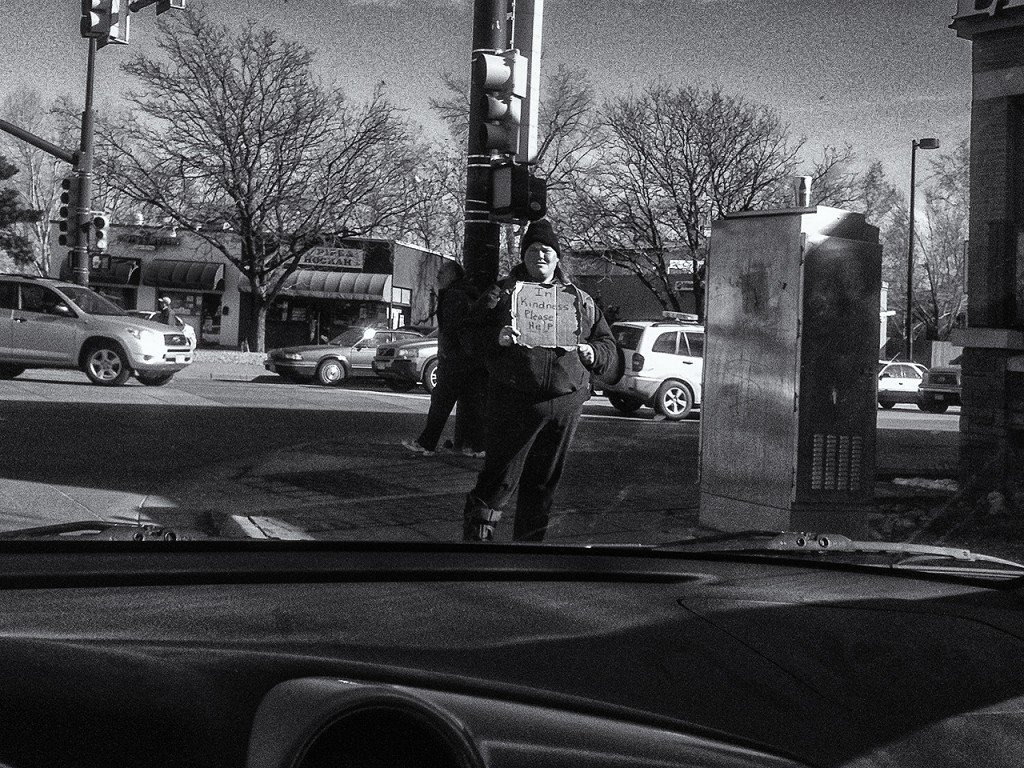

Robert Crisafi

Driving around, I am often struck by how much the car acts as a barrier between the outside world and myself. Nowhere is this more pronounced than when I drive up to a street corner where a street person is panhandling the passing drivers for some spare change. It is as if each car hermetically seals off its driver from everyone else around them. There is this sense of otherness and separation that widens the gulf between those inside the car and those outside. It’s seems like comfort and security inside, and poverty and angst outside. As such the car silently amplifies many issues inherent within contemporary society.

I include the car in this project since it is an active actor in both my experience of and detachment from the environment. By including it as a framing element, I explicitly acknowledge this role. As such it both mediates and transforms my experience with the outside. It fascinated me to include the car as a mute participant between me, the street, and the person on the corner. It seems to make me as anonymous to the people on the street as they are to me.

Some time ago I began using my I-phone (and occasionally a point and shoot) to record these brief encounters. I feel for these people because it seems that they clearly believe that standing on those corners provides their highest option for survival. Although I am fortunate to have never found myself in their position, I have experienced the anxiety of living hand to mouth. I hope that these images convey a social message around issues of privilege and poverty, have and have not, inside and outside space, public scarcity and private wealth, and other dualities that permeate our everyday lives.

Aesthetically, I see these images as creating dynamic journalistic links between social realism, urban landscape, and street photography. I especially like using an I-phone for this type of work because it adds a level of spontaneity and authenticity that could not be achieved through posed images. Like the people in the images all of the all photos remain unnamed.

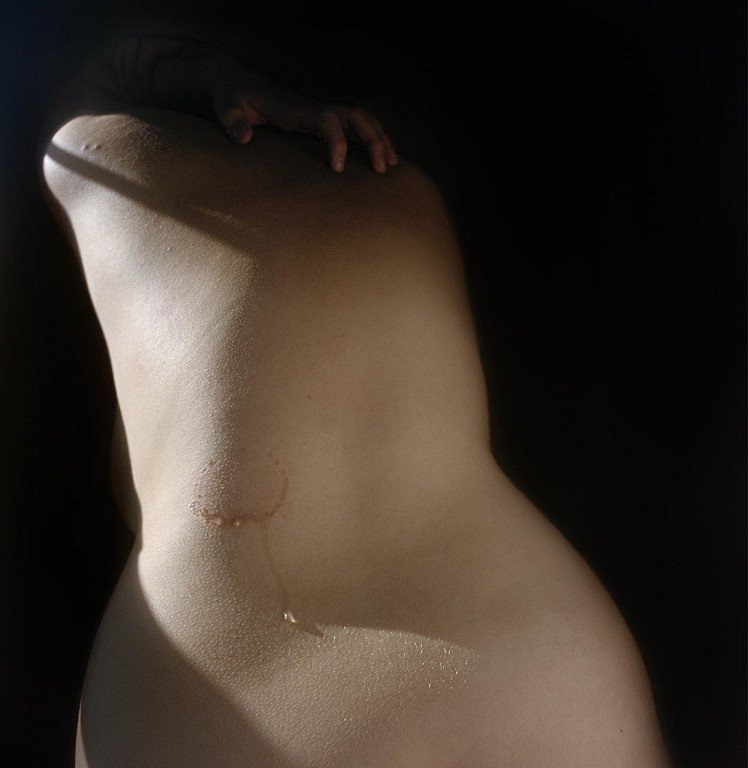

Leah Edelman-Brier

My core interests as an artist surround the female body and its portrayal, more importantly its abjection. The series ‘Body Becoming’ aims to construct beauty out of what appears outwardly grotesque while questioning the resilience of the body. The images intensify the space between youth and decrepitude as figures within the work take on the roles of mother and daughter. The daughter fears what time has done to the mother, not the mother herself. She fears the weight of flesh, the pull of gravity, the uncertainty of health, things that are set in flesh and blood.

Body Becoming in itself is an act of abjection. It repels the mother and her wilting qualities. The photographs exemplify as well as subvert abject qualities. However, the work is unclear if this ‘abject’ is truly unacceptable; and so, the series represents both sides of a coin. On one side, it embraces the abject and the ugly; on the other, it creates a subjectivity that humanizes the decay of the mother figure. Seduction and desire collide with the abject here. It creates a convoluted space where the viewer is drawn to the abject and unflinchingly senses its sexuality. Tension is created when the desirable does not align with beauty, which leaves the viewers to question their feelings towards both.

The images reveal the similarities in shape and size that the related bodies take on. The mixing notions of genetic lineage, the process of aging, and the lack of control presented by destiny, exacerbates an anxiety, which speaks to a profound fear of becoming the mother. Working against such genetics is like waging a war on nature. Witnessing this fluctuation of becoming and unbecoming within the work is like watching a fruit ripen past the point of consumption. The series pushes normative perceptions of fertility, illness, the abject, and beauty to a placed where those lines are blurred– where the decay is just as beautiful as youth.

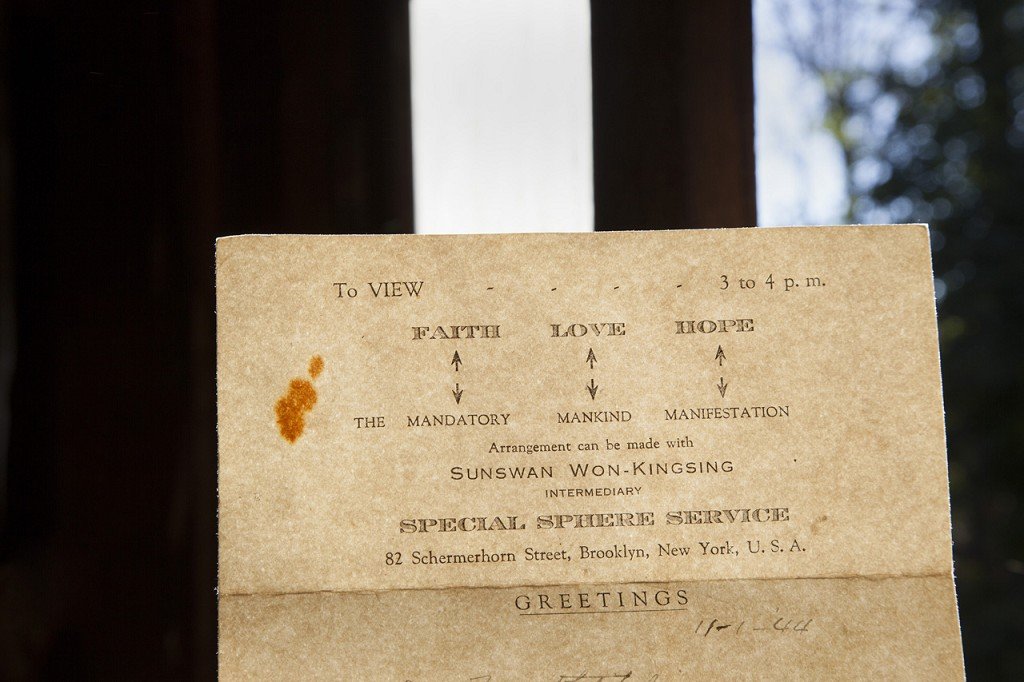

Jessica Harvey

This current project, ‘Arrows of the Dawn’, references a series of short essays and manifestos published by the Byrdcliffe Colony, which was a failed Utopian community for artists, started at the beginning of the 20th century in Woodstock, New York. While the founders had high hopes of this being a self-sustaining artist colony in tune with the Arts and Crafts movement of the time, the communal spirit cracked as tensions within the ranks grew and two of the three founding members severed ties and started their own art communities within the Hudson Valley. While Byrdcliffe failed as a Utopian vision, over 30 of the original structures still exist and the communal spirit has been revived with some of the buildings being used as an artist residency in the summer. The focus of my project is abstractly based on the story of the under-recognized matriarch of the community, Jane Byrd McCall Whitehead and her relationship to nature, spirituality, and the failed Utopian vision she had for herself and her family.

Clay Jordan

Rarely do I venture out with a topic or subject in mind—I usually drive until I see something that compels me to stop, analyze, and possibly photograph for later perusal and consideration. Over time, the editing process yields a series of images that coalesce into a body of work with specific themes or preoccupations, in this case: aging, mortality, and loss of innocence. As we age, even the most well adjusted form regrets, experience loss, and abandon certain childhood dreams. A photograph ceases to be captivating once I can explain it, so in a sense, these images are still mysteries to me, each skirting on the periphery of comprehension; some perhaps reference half forgotten memories (or dreams?) from childhood, others deal with youthful imagery now seen through the world weary eyes of an adult.

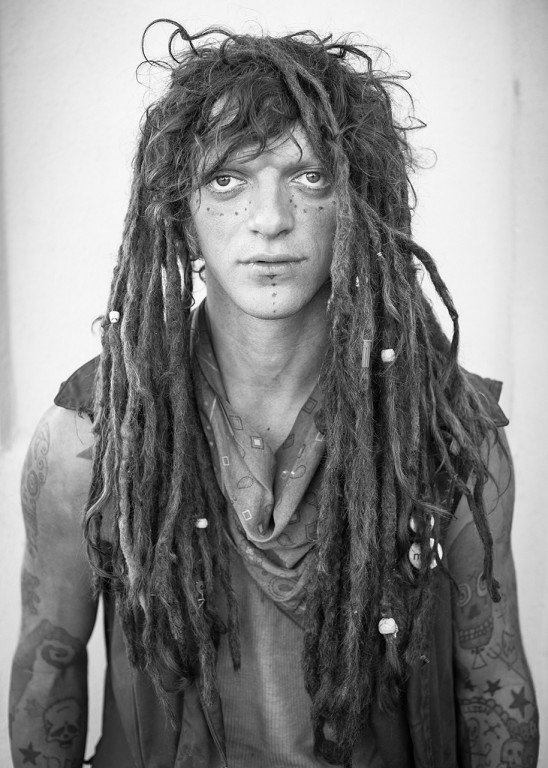

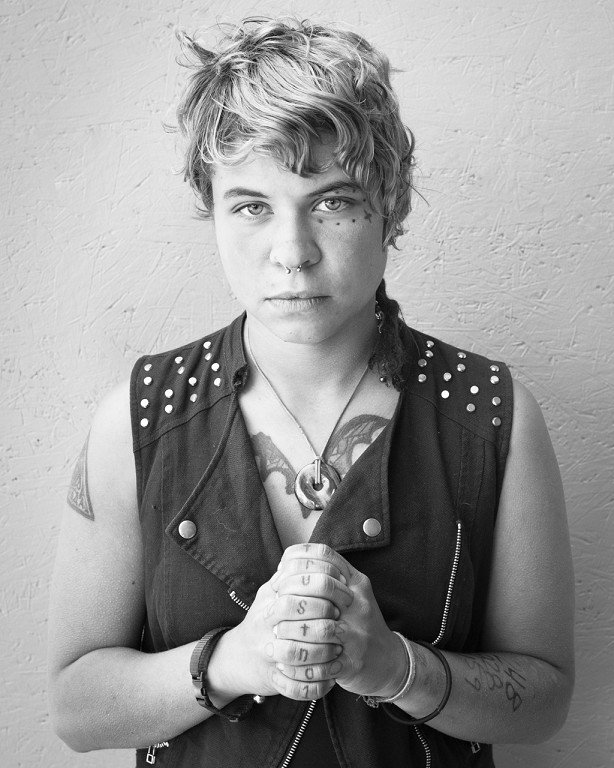

Michael Joseph

Lost and Found is a portrait series that examines the individual souls of lost youth who abandon home to travel around the country by hitchhiking and freight train hopping. Within their personal journey driven by wanderlust, escapism or a search for transient jobs, they find a new family in their traveling friends. They are photographed on public streets using natural light, in the space in which they are found.

Like graffiti on the walls of the city streets they inhabit and the trains they ride, their bodies and faces become the visual storybook of their lives. Their clothing is often a mismatch of found items. Jackets, pants and vests are self-made like a patchwork quilt, using fabric pieces of a fellow traveler’s clothing embellished by metal bottle caps, buttons, safety pins, lighter parts, syringe caps, and patches. The high of freedom however, does not come without consequence. Their lifestyle is physically risky and rampant with substance abuse.

Each traveler’s story is different, but they are bound by a sense of community. Often unseen and mistaken by their appearances, they are some of the kindest people one might meet. Their souls are open and their gift is time. As one states, “They will give you their time because time is all they have.” And in some cases, in the family they have lost, they have found each other.

Elise Kirk

I come from the middle of the country, down my own inner road between two households, where I grew up surrounded by a groundedness I couldn’t quite touch. Now I lap the nation in pursuit of an unreachable landing pad, and the middle stays with me like an anchor—a secure attachment to a Midwest myth of agrarian rootedness. Yet in my travels I encounter a different view of the region. For many, the middle states are no potential rooting ground but a place to be passed through on the way to another in our restless search for greatness.

Mid— resides in this intersection: between pulling up stakes and putting down roots, between desire and hesitation, staying and going. Here, interstate highways speed travelers and truckers past the homesteads and farm towns that have sustained kinships for time immemorial. A billboard alongside this interior stretch cries for the passersby attention. It’s more than an exit. It’s a trip.

Camilo Ramirez

I photograph the length of the U.S. Gulf Coast, investigating ways its history, economics, environment and culture intertwine to reveal a sense of displaced contradiction.

These photographs explore the nuances of the region and also include the ubiquitous use of land, animals and natural resources as they pertain to industry and recreation. The traditions, attitudes and livelihoods that are passed down through multiple generations are wound tightly into the fabric of the place and are often visible within the landscape.

Jessica Rattner

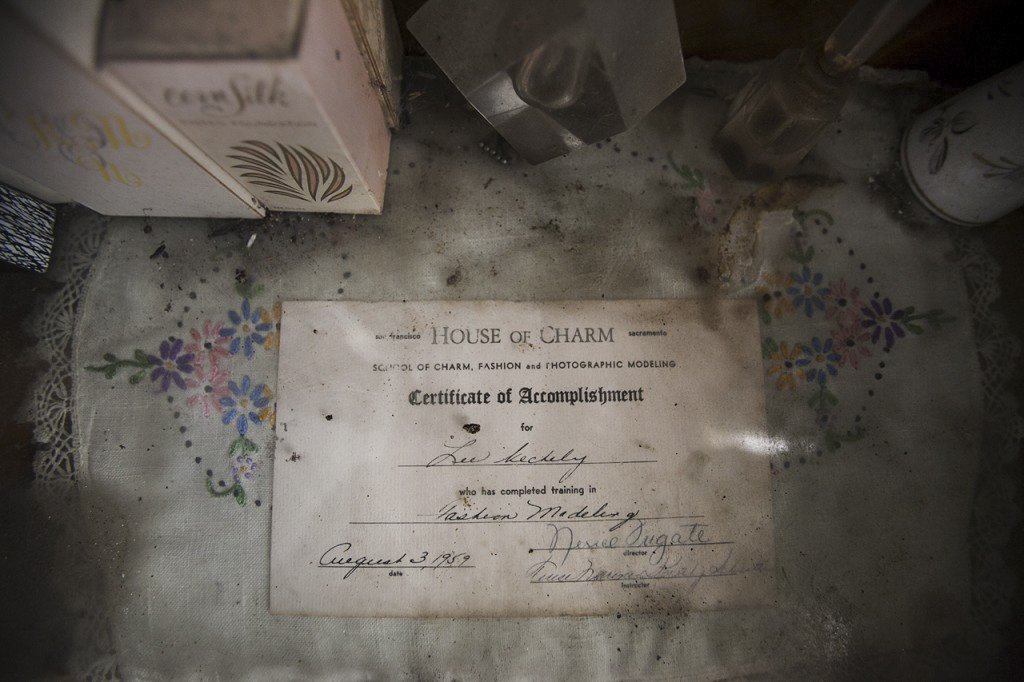

House of Charm is the ongoing portrait of Lee, an eighty year-old woman whose dirty clothes, greasy hair and dilapidated home conceal a beauty and intelligence that most people don’t easily see. It’s a story about aging alone and being di erent.

It’s also about strength, resilience, and uncommon equanimity. A former social worker, I am interested in our culture’s ideas of beauty, happiness, and mental health—especially as they relate to women. Who decides who is “crazy” and who is “sane”? Most people perceive Lee as crazy. Few get close enough to learn that while she is indeed eccentric, she is also intelligent, learned, charming, and self-assured.

When I met Lee, I was at first drawn to her colorful eccentricity, but years later it is her unusual contentment that continues to intrigue me. Without romanticizing her situation, I can’t help but wonder if Lee’s contentment in the midst of astonishing squalor, and her apparent freedom from society’s expectations, point to some secret the rest of us

Suzanne Révy

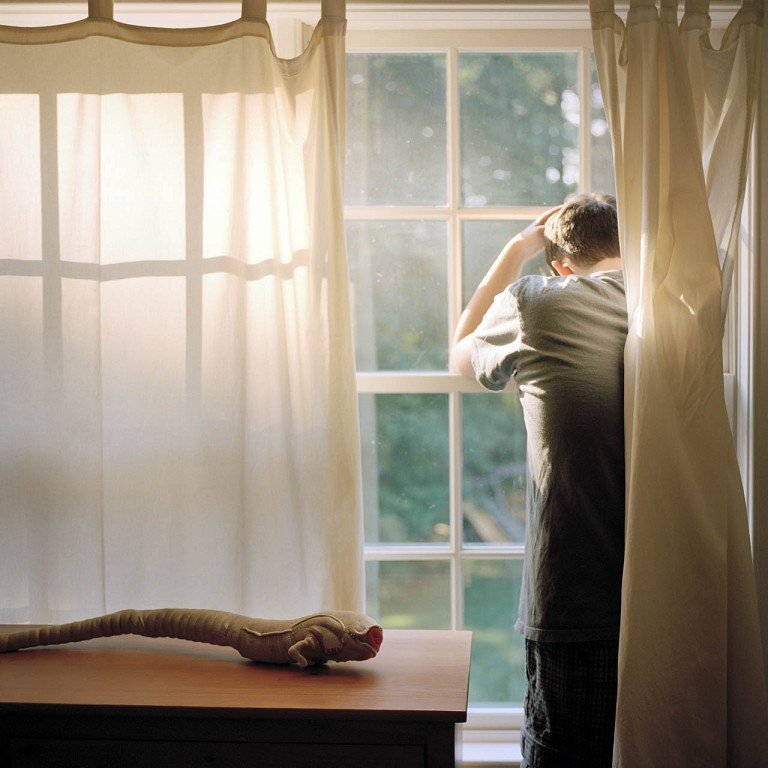

When my older son became a Bar Mitzvah, my husband and I were asked to speak to him at the end of the service. These services last about two hours, so brevity was warranted. As our children mature, such moments can be emotionally fraught for parents and finding the right words was a difficult task. I am a fan of Emily Dickinson’s poems, and when I came across the one that starts “I could not prove the years had feet,” I knew that I had found the words I was looking for. I recited this brief poem to my son on that special day.

My teenage boys seem to have gone into their rooms, and I’m not sure they’ll be coming out until they leave for college. As a parent, I have witnessed each chapter in their lives and have created a visual diary of photographs showing their creative and imaginative play, their explorations in the woods behind the house, trips to local pools or amusement parks, and—more recently—their changing bodies, interior spaces and ubiquitous technologies. They are hurtling toward an emotional departure from childhood at an alarming pace, and each chapter of their lives has proven to be fleeting and ephemeral. The selections presented here are part of a third portfolio of images that were begun when my children were toddlers. The photographs are traces of the perils and poignance in the day-to-day life of a family.

Susan Rosenberg Jones

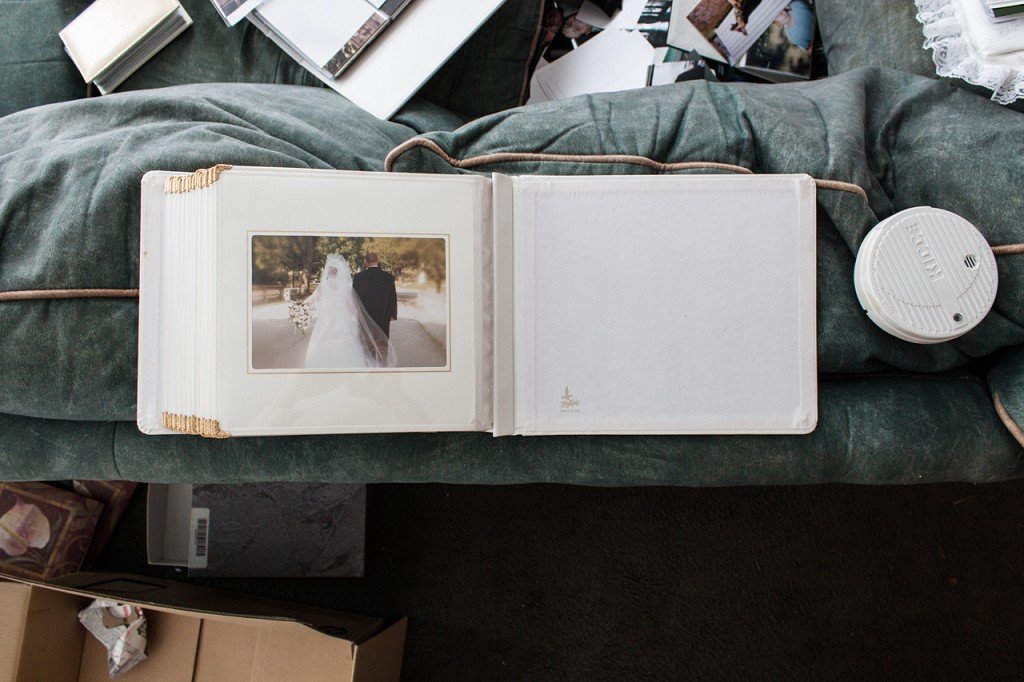

After having been married for 32 years my husband passed away in 2008, after a long illness. Once widowed, I experienced the confusing and mixed feelings of grief: guilt, loneliness, regrets, indelible memories of loving glances, hugs, and laughs. In 2009 I decided to try online dating because I wanted to meet a man for an occasional movie or dinner date.

The second man I met online was Joel, and we felt a bond right away. Soon after, I closed my account on JDate. We married in January of 2012 in a lovely ceremony at home. I hadn’t expected to fall in love, but I did. To my surprise and delight, I found that I could deeply love this wonderful man who entered my life, while holding dear the memories of my first husband.

Having been in a long-term marriage, I came to this new relationship with the tools in place to be a good wife. We quickly fell into the routine and ease of being a stable married couple, except that we were newlyweds in our 60’s. There is humor in that. For one thing, our bodies are not supple and streamlined the way they were when we were young. We both come with a lot of baggage, and at our ages, it’s no big deal, nothing to get excited about. We’ve both seen a lot, done a lot, and have higher thresholds for idiosyncratic behavior than in our 20’s and 30’s.

In this series, Second Time Around, I delight in observing my new husband as he goes about living day to day. We both know that life is short, and perhaps because of our new found love and comfort, can journey through this life with a certain enthusiasm. We feel secure, yet we know we’re lucky

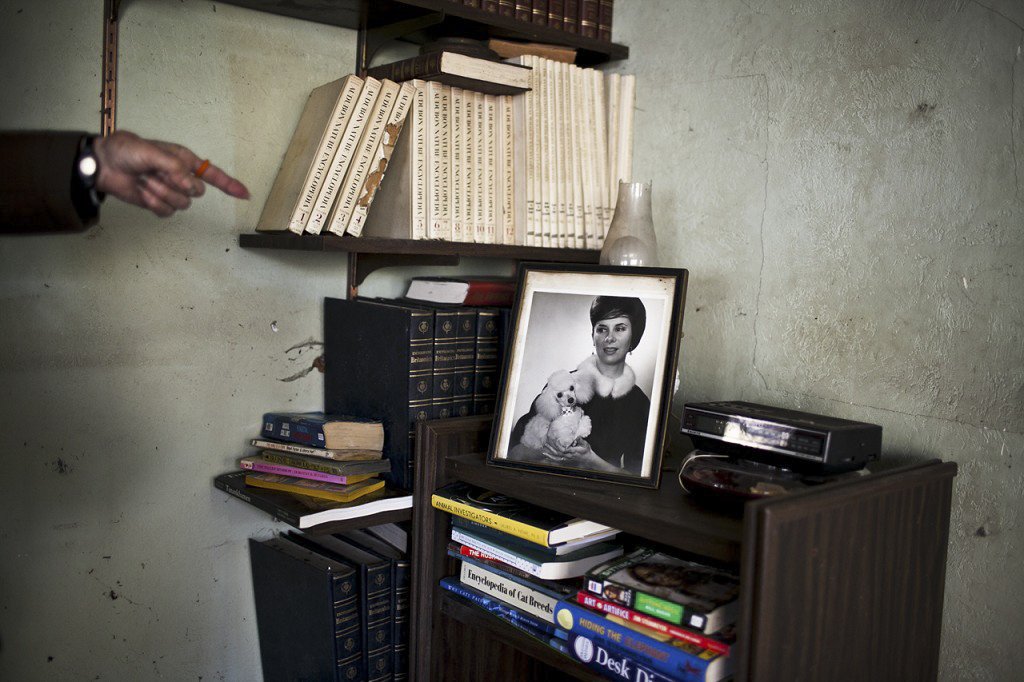

Joseph Stanek

It’s no secret that after the market crash of 2008 foreclosed and abandoned homes have become an issue in the United States. As a real estate professional that specializes in these properties, I often find myself in vacant homes, among abandoned items, allowing me to look back at the lives of those who once lived there.

Through Left Behind, I explore unique items that homeowners have abandoned. The items need not be of monetary value, but serve as an adjective in the story that was the home.

Once left behind, these items have a limited lifespan. They most assuredly will be discarded in the trash—out of the property as it is prepared for sale to new owners. As you read this, undoubtedly most of these items have already been tossed away, and because of this, the story you choose to attach to each item cannot be proven to be wrong…

Taylor

Growing up in the flatlands of Chicago, the first hill I fell in love with was manmade, our only so-called “mountain”. It provided hours of sledding and sliding in the winter and running, rolling and pretending in the summer. As a result of these experiences, I longed for “real landscapes” with drama and challenges like the majestic mountainous terrains I saw in old Western films and Ansel Adams’ photographs.

As soon as I was able, I moved west to California where my longing for more invigorating landscapes was at last satisfied. I became increasingly interested in the complex relationships between humans and their environments, and in questions of what constituted Nature. Still captivated by the mound of my childhood, I began to seek out and find all kinds of manmade hills in my newfound environment. The remains of roadbuilding, construction, or the byproducts of mines and quarries, they came in a wide variety of shapes, sizes and materials. Often isolated in flat desolate surroundings, it was likely that few people came to either contemplate or appreciate their silent beauty.

My photographs capture these landforms, devoid of vegetation, architecture or any overt forms of human life, ambiguous in their identities, locations, weather conditions and scale. In addition to the structures of the mounds themselves, traces of human presence remain evident in occasional white trails in the sky. These simple landscapes are enthralling yet foreboding to me, as they simultaneously represent fond memories as well as ongoing manmade intrusions into natural habitats.

JP Terlizzi

The hunt is most often defined by its final explosive moment. The flash, the blast, the crack as the bullet slices through the air. But in truth, it is the time before the trigger is pulled – hours that are mindful, silent and elongated – that is sacred to the hunter.

The kill is a culmination. The hunt is its rich prelude, mindful and satisfying, ritualistic and grittily romantic. The true reward lies in the communion between hunter and prey.

Through this work I delved into this primal relationship, and witnessed an interaction driven by instinct and cunning; hunter and prey engaged in an ancient contest of skill and survival, with raw landscape as a backdrop. I observed a group of young men united by the desire to connect with their surroundings, who understand and interpret the story of the woods. Their mission is not one of violence, but one of appreciation of a worthy adversary, a respect for tradition, and a reverence for the hunt.

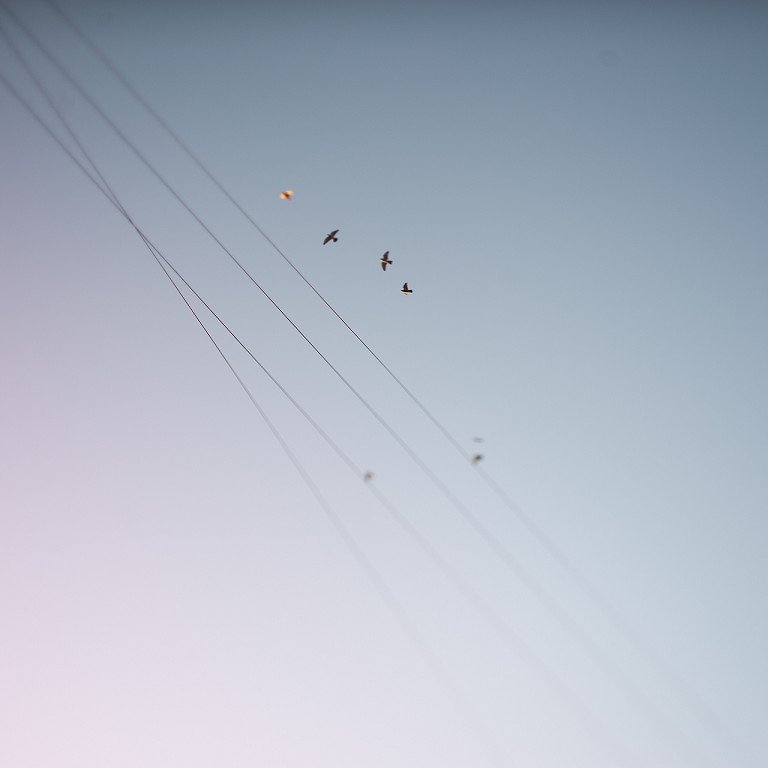

Leah Zawaszki

There something about the passing of time, moments seem to go by before they even begin. Time is a reoccurring theme that plays out in many artists’ minds. There is a constant tension between past and future, making the effort to stay in the present often a difficult task. Leah Zawadzki is drawn to these fleeting moments. She photographs them in a meditative, almost therapeutic way to overcome this struggle. With that, there is a bit of happenstance that occurs, but the theme of time passing continues to dominate. Something as simple as a child’s hand picking a cherry during a season that is very short lived, can be seen as a metaphor for this season in her own life. This series is an exercise of wandering and seeing what the world has to tell. Even though moments are fleeting, love is a constant and always remains. This is a collection of photographs about love, family, home and being present.