EXHIBITION DETAILS

In Conversation with the Land

September 3 - December 31, 2021

Outdoor Projections: September 4, 2021

Curated by Karen Haas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Selected Artists: Paul Adams, Matthew Arnold, Nancy Baron, Bremner Benedict, Megan Bent, Brenda Biondo, Donald Black Jr, Cecilia Borgenstam, Lily Brooks, Annette LeMay Burke, Zintis Buzermanis, Edgar Cardenas, JoAnn Carney, Mima Cataldo, Diana Cheren Nygren, Julianne Clark, Patrick Corrigan, Marco Corvo, Shannon Davis, Frank Day, Alfredo De Stefano, Anne Eder, David Ellingsen, Jim Ferguson, Teri Figliuzzi, William Franson, David Gardner, Daniel George, Jessica Marie Gross, Julya Hajnoczky, Drew Harty, Charlotta Hauksdottir, Beth Johnston, John Kane, Kent Klaudt, Linda Kuehne, Molly Lamb, Tanya Lunina, Holly Lynton, Cheryl Medow, David Moenkhaus, Susan Patrice, John Puffer, Suzanne Révy, Conohar Scott, Carol Sogard, Maximilian Thuemler, Alex Turner, Ira Wagner, Becky Wilkes.

Awards:

Juror’s Award: Bremner Benedict

Director’s Award: David Ellingsen

Honorable Mentions: Matthew Arnold, Patrick Corrigan, Daniel George, Charlotta Hauksdottir, Holly Lynton, Suzanne Révy, Maximilian Thuemler

JUROR’S STATEMENT

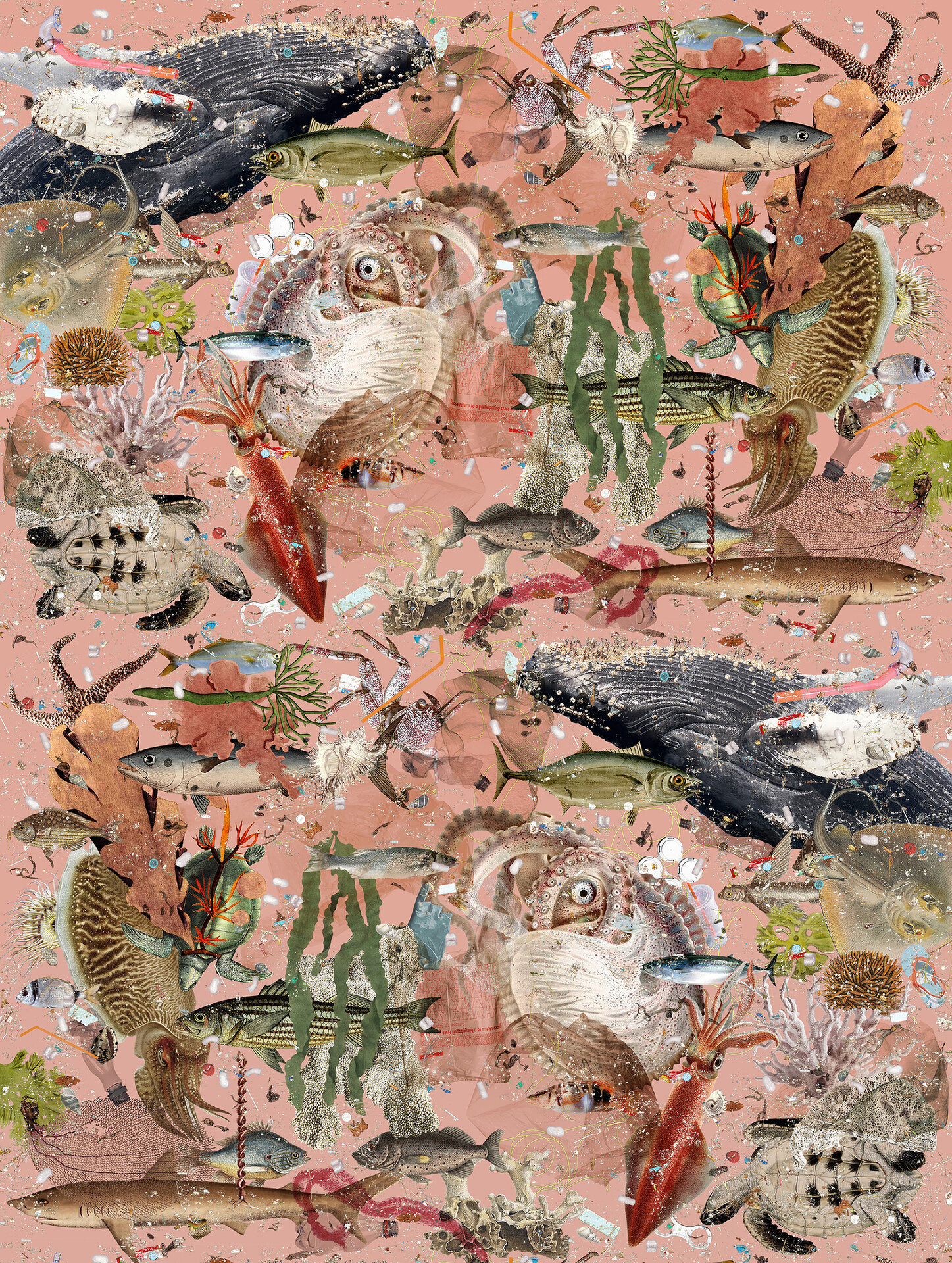

This exhibition’s title—In Conversation with the Land—may conjure up images of untouched wilderness and pristine nature, but what inspires many of the artists in the show is a desire to chronicle the lasting impact and irreversible harm that we as humans have inflicted on our planet. These fifty photographers speak to our fragile and complex relationship to the natural world using a wide variety of styles and employing very different means. Some have chosen to take a very distanced, “macro” approach to their subjects with sweeping aerial views, panoramas, and multipartite prints, though even more seem drawn to a microcosmic vision and focus instead on a lone tree, suburban house, or endangered species. Several have bypassed the digital capture to express their ideas in the form of chlorophyll, lumen, and cyanotype prints, while a few compulsive collector-gatherers have created striking botanical studies, taxonomies, and collages out of everything from foraged mushrooms and junk mail to the accumulation of trash collected along a particular shoreline.

In some memorable cases, the landscape in these photographs is visually “excavated,” as an archeologist might do: to better understand the soil, the scale, the history, and even the trauma of human interactions that have been witnessed there. In other instances, nature is employed as an expressive language that allows an artist to explore very personal memories or express deeply felt spiritual connections to a site. A number of these visual records of the land leave out the human presence altogether, although the telltale signs of its inhabitants—past and present—are seemingly everywhere. Often it is those very subtle traces that help retell the sometimes painful narratives attached to a place and point to the damaging practices that have marked or changed it over time.

Like many others, I have found it very challenging to separate my work life from our collective experience of the Covid pandemic, so it should have come as no surprise to me that so many of the photographs represented here speak to the urgent issues of this moment—from concerns about climate change and global warming to our long-overdue racial reckoning, and from immigration and borders, wild fires, and urban sprawl to social challenges related to mental health and homelessness. As a photo curator based in New England, I have also come to realize that the desert landscape is an especially magical place for me—in many ways more alien and intriguing than any distant locale I’ve ever visited. That fascination with an environment so unlike my own is what initially drew me to choose Bremner Benedict’s “Hidden Waters” series for the Juror’s Selection award. Benedict’s multi-year-long project centers on the issue of water scarcity and endangered eco-systems in this country’s arid west and southwest. What keeps me coming back to these photographs is not simply their compelling subject matter, but their delicate palette, richly varied compositions, and the artist’s acknowledgment of the long history of indigenous peoples and changing land use in these regions.

Many thanks to Hamidah Glasgow and her colleagues at the Center for Fine Art Photography and especially to all of those who submitted the consistently strong works that I had such pleasure reviewing.